New Voices RGU Student Series: Robyn Orr

Category: New Voices

This blog is posted as part of our New Voices RGU Student Series, where we are publishing blogs written by Robert Gordon University Information and Library Studies Students as part of their coursework.

About the writer: Robyn Orr is a Library Assistant in Special Collections and Archives at the University of Liverpool Library. She is currently studying MSc Information and Library Studies at Robert Gordon University. Her professional interests are the facilitation of information literacy skills, “Library Anxiety”, and outreach development within a Special Collections and Archives context.

The “equivalent of a medieval monk”?: The role of higher education Special Collections and/or Archives professionals in facilitating information literacy skills

Within my role as a Library Assistant, I supervise the handling of rare books and archives used within academic teaching. Whilst introducing me to students using medieval manuscripts, the module leader announced, “this librarian is the equivalent of a medieval monk! Only she knows where the books are held within the bowels of the building, and you can read them at only her command!”

This evocative introduction actively demonstrates a challenge facing the Special Collections and/or Archives (SCA) professional: a curious dichotomy exists, in that the popular perceptions of SCA professionals and services is at odds with the available expertise in facilitating information literacy (IL) skills. There are varied models available for defining IL, however the Society of College, National and University Libraries Seven Pillars Model is designed for the higher education context; it refers to the ability to “gather, use, manage, synthesise and create information and data in an ethical manner” (2011 p. 3). Further, it is vital to consider primary source literacy and digital literacy as part of the necessary IL skills package to utilise SCA services.

On the one hand, SCA professionals can be presented in media as the guarded “keepers” of rare books and archives (Oliver and Daniel, 2015). Similarly, many SCA departments operate a closed stack system, whereby users are unable to browse and must book an appointment. However, SCA professionals are keen to promote the existence, importance, and accessibility of primary material as part of teaching and research (Koda, 2010). Students’ ability to understand how to independently evaluate and critically select records within SCA catalogues (often available digitally as an Online Public Access Catalog, or OPAC) is therefore vital to their ability to access the primary sources themselves (Roff, 2007); this proficiency is christened “Archival Intelligence” by Yakel and Torres (2003, p. 52).

The SCA professional is the natural facilitator in equipping students with the IL skills to access and use primary sources. As identified by Vassilakaki and Moniarou-Papaconstantinou (2017), there is a wealth of literature regarding the educational role of the archivist. SCA professionals also function as teachers, and their involvement in undergraduate teaching imparts a proven benefit in improving IL (Miller 2012). Within the realm of primary source literacy, frameworks have been developed to aid the professional in establishing pedagogy. Carini asserts that a framework is necessary to “introduce students not just to subject-based materials but also to how to find, interpret, and create narratives using primary sources” (Carini 2016 p. 196). Further, flexible guidelines to develop learning objectives for those teaching IL skills in the primary source environment have been published as a result of the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Rare Book and Manuscript Section and Society of American Archivists Joint Task Force (2017).

This poses the question: how can SCA professionals effectively utilise frameworks to enable students to ‘see past’ the role stereotypes and access conditions of SCA material? There is no single answer; many professionals will understand their role within the parameters of their institution. However, two general suggestions are helpful. Firstly, SCA professionals in frequent contact with students should embrace continuing professional development opportunities to ensure that they are trained educators, a skill set identified by Krause (2010) as wanting within the archive profession. Secondly, SCA information professionals should consider a multi-faceted approach: hosting sessions in collaboration with academics, demonstrating active engagement with catalogue records, handling of primary material, and teaching within SCA environments (Krause, 2010; Johnson, 2006). The potential to assist students in developing their information literacy skills is perhaps as valuable as the unique primary sources themselves. In which case, being compared to a “medieval monk” is a small price to pay!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION, 2018. Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy Developed by the ACRL RBMS1 -SAA2 Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy [Online] Available from: http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/Primary%20So urce%20Literacy2018.pdf [Accessed 19 October 2019]

CARINI, P., 2016. Information Literacy for Archives and Special Collections: Defining Outcomes. Libraries and the Academy, 16(1), pp. 191-206.

JOHNSON, G., 2006. Introducing Undergraduate Students to Archives and Special Collections, College & Undergraduate Libraries, 13(2), pp. 91-100.

KODA, P., 2008. The Past Is More than Prologue: Special Collections Assume Central Role in Historical Research and Redefine Research Library. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 78(4), pp. 473-482.

KRAUSE, M., 2010. “It Makes History Alive for them”: the Role of Archivists and Special Collections Librarians in Instructing Undergraduates. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(5), pp. 401-411.

MILLER, M., 2012. Information Literacy Instruction and Archives & Special Collections: A Review of Literature, Methodology, and Cross-Disciplines. Second Annual International Conference on Information & Religion [Online] Available from: https://digitalcommons.kent.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=acir [Accessed 19 October 2019].

OLIVER, A. and DANIEL, A., 2015. The Identity Complex: The Portrayal of Archivists in Film. Archival Issues, 37(1), pp. 48-70.

ROFF, S., 2007. Archives, Documents, and Hidden History: A Course to Teach Undergraduates the Thrill of Historical Discovery Real and Virtual. The History Teacher, 40(4), pp. 551-558.

SOCIETY OF COLLEGE, NATIONAL AND UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, 2011. The SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy Core Model For Higher Education, London, UK: SCONUL. Available from: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/coremodel.pdf [Accessed 19 October 2019]

UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL LIBRARY, 2017. Photograph of the archive store stacks. Unpublished photograph.

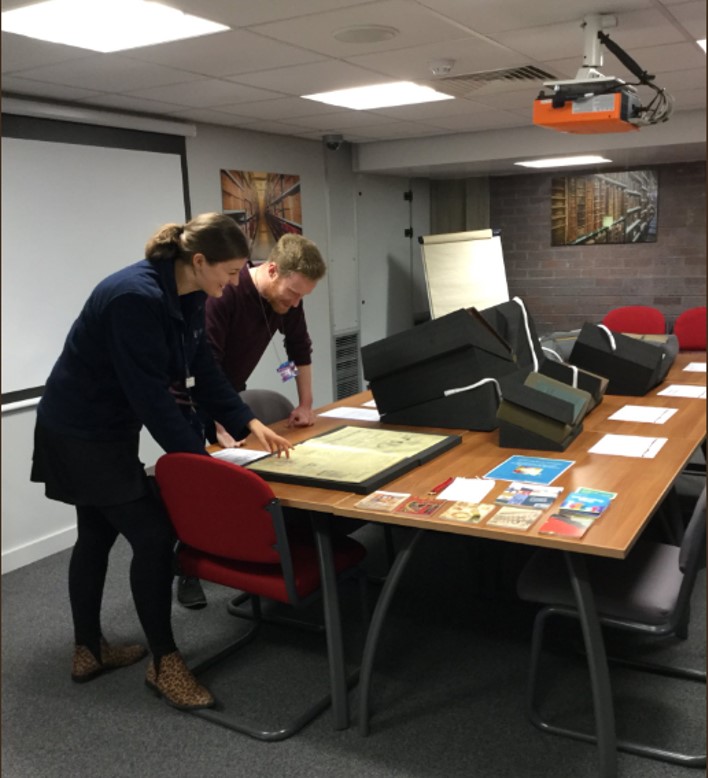

UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL LIBRARY, 2017. Photograph of primary source teaching session. Unpublished photograph.

VASSILAKAKI, E. and MONIAROU-PAPACONSTANTINOU, V., 2017. Beyond preservation: investigating the roles of archivist. Library Review, 66(3), pp. 110126.

YAKEL, E. and TORRES, D., 2003. AI: Archival Intelligence and User Expertise. The American Archivist, 66(1), pp. 51-78.

YAKEL, E., 2004. “Archives and manuscripts information literacy for primary sources: creating a new paradigm for archival researcher education”. Library Perspectives, 20(2), pp. 61-64.

YAKEL, E., 2004. “Encoded archival description: are finding aids boundary spanners or barriers for users?”. Journal of Archival Organization, 2(1&2).

**The views expressed in our guest blogs are the writer’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of CILIPS**