‘the tottie wee miracles that string thegither…’ CILIPS 2023 Conference | Thomas Clark

Branch: West Branch | Category: Blog, Branches and Groups

Thomas Clark, a Librarian for North Lanarkshire Libraries, received a sponsored place at the CILIPS 2023 Annual Conference from CILIPS West Branch. Read on to discover his experience of attending the Conference. Thomas, as well as being a Librarian, is a published author of many titles in Scots so he’s given us his blog post in both in Scots and English.

A Maitter o Trust

There are things, in ony line o wark, that ye accommodate yersel tae, aften tae the extent that ye simply stop noticin them. Like the air we breathe in, they’re that ubiquitous that ye jist forget aw aboot them. Sometimes, it’s the guid things – the tottie wee miracles that string thegither wan oor tae the next, the moments o connection, the opportunities for kindness. Sometimes, it’s the bad – stress, unfairness, the pain o ithers. An it’s anely when ye’re in a room full o ither fowk sharin their ain experiences o the profession that ye realise these wee details – unseen, unkent – are aften whit adds up tae somethin mair than a career. A callin, likesay.

Sae, for me, the opportunity tae gang tae the CILIPS Conference in Dundee wisnae jist a chance tae reflect on guid policy an best practice. It wis a chance tae be reminded whit ah’m in it for – whit wad be lost if aw the librarians in the warld jist ran awa an jyned the Navy, as ah dout we maun aw be sairly tempted tae dae, sometimes. Whit things we dae that, but for us, wad bide unduin. Whit guid we bring aboot, aften withoot even kennin it.

An whit came hame tae me, throughoot ma day at conference, wis thon value – aft unspoken o, aft unminded – that libraries bring sae continually an consistently intae bein. That o trust.

Nane o the keynotes or sessions ah attendit were explicitly aboot trust, or even mentioned it. But for aw that, time an time again ah wis mindit that, against a backdrap o erodin public faith in institutions o aw kinds, the public library remains a kenspeckle ootlier – a public service trustit by aw, frae the big high-heid-yins richt through tae oor maist vulnerable citizens. We dinnae need the research that shows us it (or we shouldnae) – we see it for oorsels, every day. Libraries, in public perception, might be wheesht or lood, quiet or thrang, full o books or hoachin wi computers – but the wan thing they are, above aw, is safe. Tae the bairns and parents at Bookbug, the buddin memmers o oor codin clubs; tae the hameless, the vulnerable, the refugees, the alane; libraries mean safety.

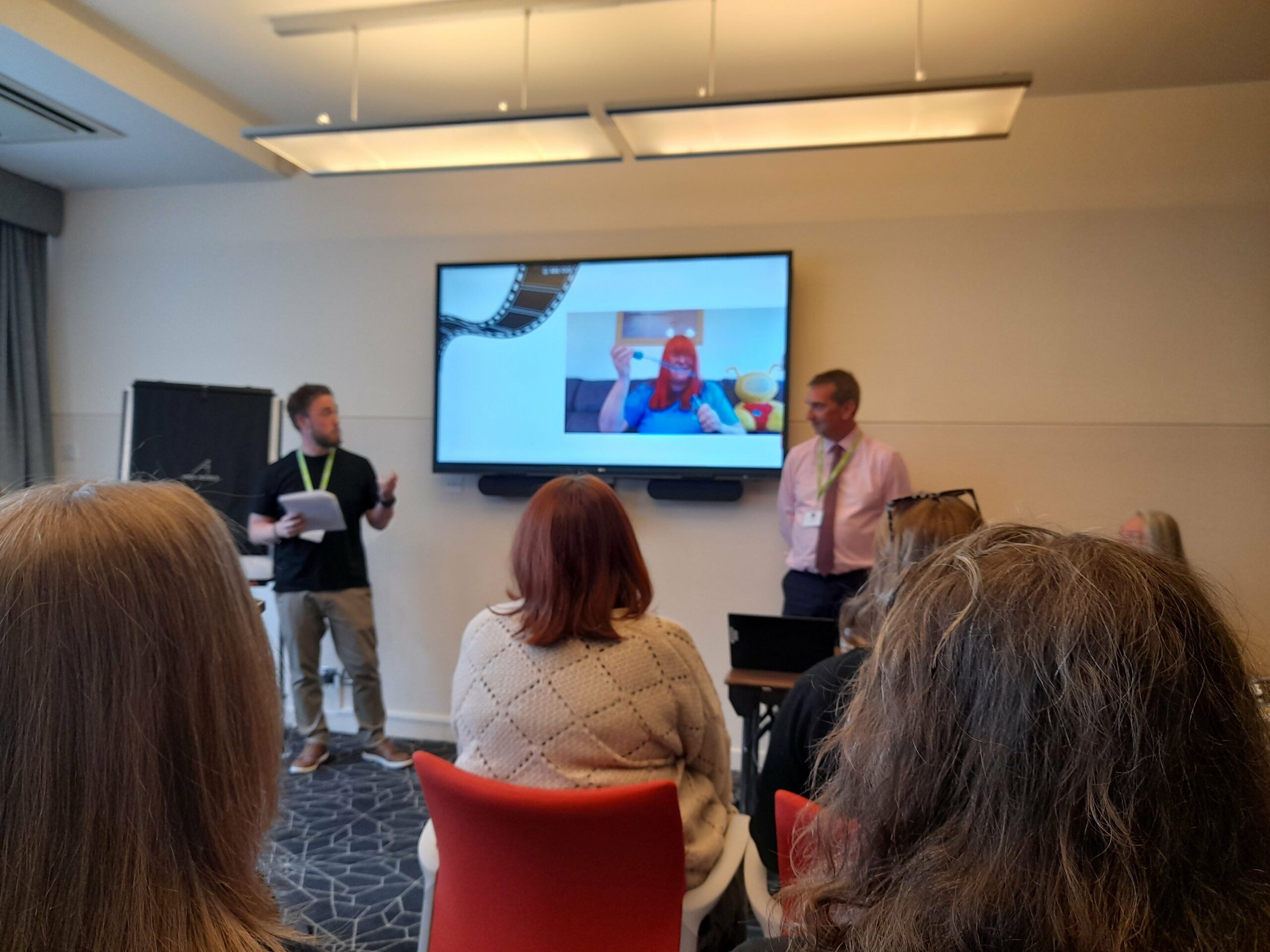

An every session ah sat in on at conference wis, wan wey or anither, aw aboot thon public trust. Tak the parents o Sooth Lanarkshire Cooncil. The lockdoon, tae them, meant an unjoukable rise in the amoont o screentime their bairns were subject tae. Thon couldnae be helped. But wha could they trust tae mak shair that thon screentime was safe, an healthy, an no jist anither thing they had tae wirry aboot durin the maist stressful period o their lives? They could trust Sooth Lanarkshire Libraries, and their smashin, prodigious ootpit o online Bookbugs, education videos, an digital pantomimes.

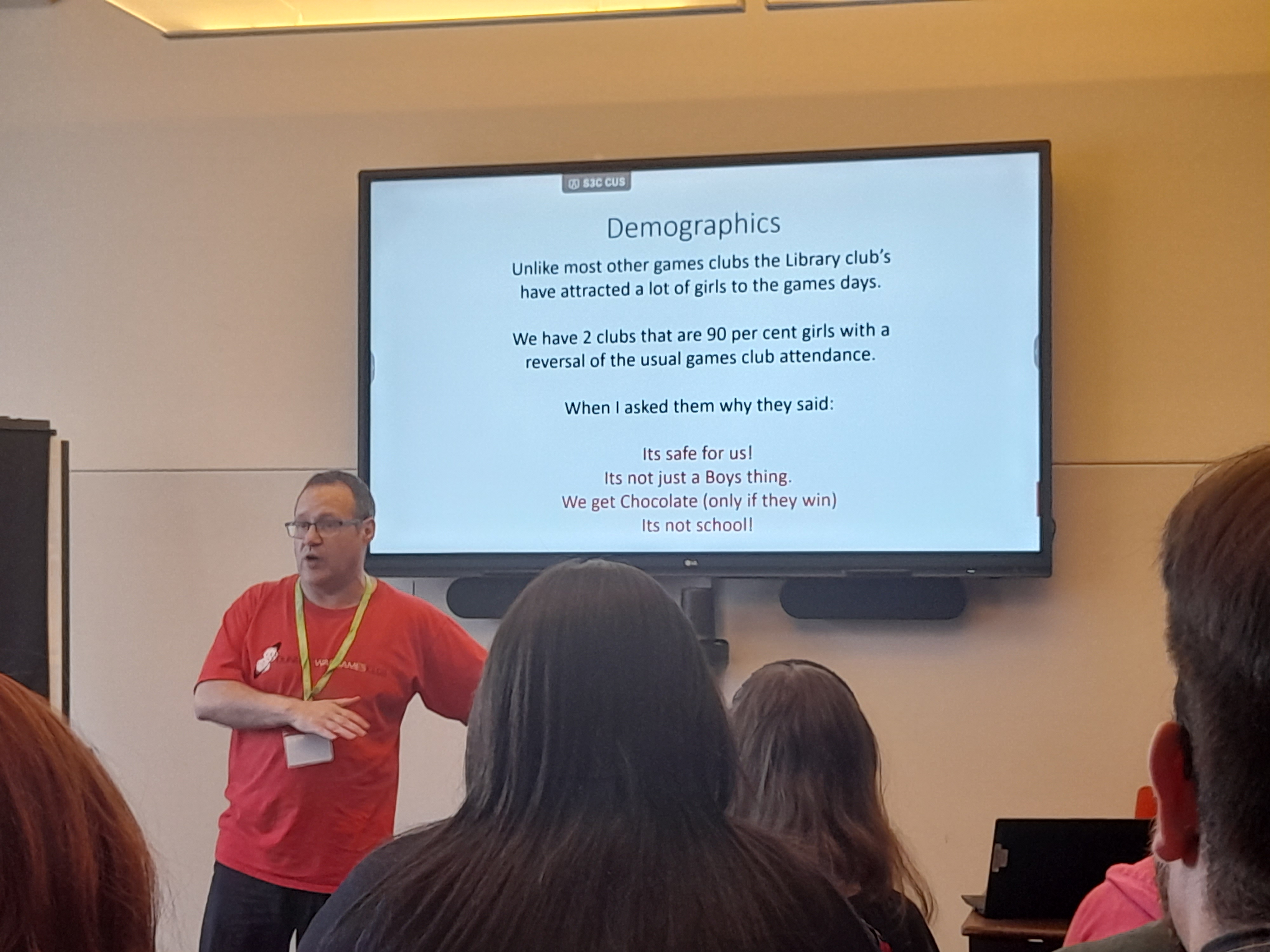

Or tak the young fowk o Dundee. Wha can they trust tae tak them as they are – no jist as customers or consumers, but as human beins, no jist as pootches full o unspent pocket money, but as precious resoorces themsels ayont aw price? Weel, they can trust the tabletap gamin groups o Dundee Libraries, whaur awthin but awthin is free, includin their choices, their time, an – sometimes – their chocolate.

Public trust in libraries is somethin that we tak for grantit. We shouldnae. It’s ower easy tae forget whit a ferlie thing thon trust is; how hard-won, how easily lost. An inherent tae it aw is that thon trust is aye reciprocal. Frae the meenit they’re auld eneuch tae ken a Lorax frae a Gruffalo, a library uiser is treatit first an foremaist as somebody wha kens best whit’s best for them, as a self-directit reader an lairner, an independent thinker, and a significant participant in a significant community.

In a warld whaur oor consumer choices are becomin less an less meaninfu – this phone case or that yin, ain-brand or luxury, decisions that reflect anely the limits o oor means, no the limits o oor howps or aspirations – the public library stauns (in mony toons, onywey) alane. A place whaur a body can gang, no tae be telt whit’s wrang wi them an how much it’ll cost tae fix it, but tae be fully supportit in wha they are an whit they howp tae become.

The Dewey nummer for sociology, the login passwird for Windaes – aye, these are things easy eneuch tae forget. But easier still is the joy o wirkin wi sic fowk in sic places. Thanks tae awbody at the CILIPS conference for helpin me tae remember.

A Matter of Trust

There are things, in any line of work, that you accommodate yourself to, often to the extent that you simply stop noticing them. Like the air we breathe in, they’re so ubiquitous that you just forget all about them. Sometimes, it’s the good things – the tiny wee miracles that string together one hour and the next, the moments of connection, the opportunities for kindness. Sometimes, it’s the bad – stress, unfairness, the pain of others. And it’s only when you’re in a room full of other people sharing their own experiences of the profession that you realise that those small details – unseen, unknown – are often what adds up to something more than a career. A calling, for instance.

So, for me, the opportunity to go to the CILIPS Conference in Dundee wasn’t just a chance to reflect on good policy and best practice. It was a chance to be reminded of what I’m in this for – what would be lost if all the librarians in the world just ran away and joined the Navy, as I’m sure we must all be sorely tempted to do, sometimes. Those things we do that, but for us, would remain undone. The good we bring about, often without even knowing it.

And what came home to me, throughout my day at conference, was that value – oft unspoken of, oft unremembered – that libraries bring so continually and consistently into being. That of trust.

None of the keynotes or sessions I attended were explicitly about trust, or even mentioned it, really. But for all that, time and time again I was reminded that, against a backdrop of eroding public faith in institutions of all kinds, the public library remains a proud outlier – a public service trusted by all, from the biggest of bosses right through to our most vulnerable citizens. We don’t need the research that shows us it (or we shouldn’t) – we see it for ourselves, every day. Libraries, in public perception, might be silent or loud, quiet or busy, full of books or stowed out with computers – but the one thing they are, above all, is safe. To the children and parents at Bookbug, the budding members of our coding clubs; to the homeless, the vulnerable, the refugees, the alone; libraries mean safety.

And every session I sat in on at conference was, one way or another, all about that public trust. Take the parents of South Lanarkshire Council. The lockdown, to them, meant an unavoidable rise in the amount of screentime their children were subject to. That couldn’t be helped. But who could they trust to make sure that that screentime was safe, and healthy, and not just another thing they had to worry about during the most stressful period of their lives? They could trust South Lanarkshire Libraries, and their awesome, prodigious output of online Bookbugs, education videos, and digital pantomimes.

Or take the young people of Dundee. Who can they trust to take them as they are – not just as customers or consumers, but as human beings; not just as purses full of unspent pocket money, but as precious resources themselves beyond all price? Well, they can trust the tabletop gaming groups of Dundee Libraries, where everything but everything is free, including their choices, their time, and – sometimes – their chocolate.

Public trust in libraries is something that we take for granted. We shouldn’t. It’s too easy to forget what a marvel that trust is; how hard-won, how easily lost. And inherent to it all is that that trust is always reciprocal. From the moment they’re old enough to know a Lorax from a Gruffalo, a library user is treated first and foremost as somebody who knows best what’s best for them, as a self-directed reader and learner, an independent thinker, and a significant participant in a significant community.

In a world where our consumer choices are becoming less and less meaningful – this phone case or that one, own-brand or luxury, decisions that reflect only the limits of our means, not the limits of our hopes or aspirations – the public library stands (in many towns, anyway) alone. A place where a person can go, not to be told what’s wrong with them and how much it’ll cost to fix it, but to be fully supported in who they are and what they hope to become.

The Dewey number for sociology, the login password for Windows – yes, these are things easy enough to forget. But easier still is the joy of working with such people in such places. Thanks to everybody at the CILIPS conference for helping me to remember.