Carnegie and the History of Scottish Public Libraries

Category: #Carnegie100, Blog

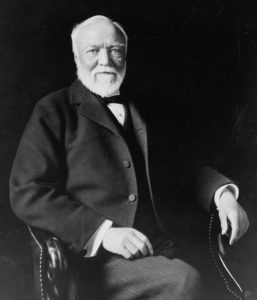

This blog post is part of our #Carnegie100 series, marking the 100th anniversary of Andrew Carnegie’s death and celebrating his libraries legacy.

Andrew Carnegie and his place in the history of Scottish public libraries

by Professor Peter Reid, Robert Gordon University

“A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.” – Andrew Carnegie

“A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.” – Andrew Carnegie

From the 1880s onwards, the public library landscape changed radically because of the intervention of one benefactor, Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919).

Public Libraries before Andrew Carnegie

Throughout the nineteenth century, the movement for social and political reform gathered momentum and a strong movement in favour of the provision of free public libraries emerged. The fundamental principle which this movement held to was universal access to books and to reading materials, not just for those wealthy enough to afford to have their own collections. William Ewart, MP for Dumfries Burghs, was instrumental in bringing the Public Libraries Act of 1850 to the Statute Books. Ironically, however, it did not apply to Scotland, despite Ewart sitting for a Scottish constituency. Three years later, in 1853, the Public Libraries (Scotland) Act was passed which allowed burghs to raise the rate by 1d and to spend the revenue generated on library and museum buildings as well as collections for them. The Scottish Act enabled the rates increase to be approved by a two-thirds majority at a public meeting of those who owned or occupied a house valued at £10 per annum or more.

Andrew Carnegie and Public Libraries

Carnegie’s family emigrated from Scotland to the United States in 1848. His first job was in a bobbin factory; later he became a telegraph messenger and steadily rose through the ranks of that company. Eventually, he went into the steel industry and ultimately created, after a series of mergers and takeovers, US Steel, one of the biggest and most successful companies the world has ever known. His wealth at its peak has been estimated at around $300 billion in contemporary values.

His first public library was the Carnegie Library in his home-town of Dunfermline which was opened in August 1883. It was the success of this library in Dunfermline which proved the catalyst for his decision to fund library building throughout the English-speaking world. By the time of his death in 1919, there were more than 2,500 Carnegie Libraries, many of them in his home country. Edinburgh, as has been noted, was decidedly reluctant to adopt the Public Libraries Act and, indeed, it was the last city in Scotland to do so. Carnegie initially offered £25,000 to Edinburgh which he then doubled, helping to overcome lingering opposition in the capital to a public library service. Carnegie laid the foundation stone for the library, on George IV Bridge, in 1887. At the opening, three years later, a message from Carnegie was read out. It said “we must trust that this library is to grow in usefulness year after year and prove one of the most potent agencies for the good of the people for all time to come”.

Andrew Carnegie: Approach and Attitude

This attitude was central to Carnegie’s approach. He had fixed views about wealth and philanthropy and famously declared in his book The Gospel of Wealth that a man who dies rich dies disgraced. As a consequence, he was determined to use his enormous wealth for the greater good of society. He had a strong attachment to learning, self-improvement and education, and all of these formed the cornerstones of his philanthropy. Libraries played part because of the affection for, and gratitude to, the libraries which he himself had been able to use during his formative years. His underlying philosophy to life helps explain much about his philanthropy. He said that a man should spend the first third of his life getting all the education one can, spend the next third making all the money one can and spend the last third giving it all away to worthwhile causes.

Thanks to Carnegie, the period from the mid-1880s through to the First World War became a felicitous time for public libraries. Carnegie was, however, stringent in his requirements of councils through, what came to be called the ‘Carnegie Formula’. This required that councils had to demonstrate clearly that there was a need for a public library, they had to provide the site, contribute ten percent of the cost of construction and support its running costs (for which Carnegie rarely gave money). Most importantly, as far as Carnegie was concerned, it had to provide a free and universal service. It was Carnegie’s staunch belief that the recipient towns had to show an ongoing commitment to maintain and enhance the library. Without that, he would walk away and, indeed, on some occasions, he did just that. The ethos of building and maintaining libraries had also been enshrined in the 1887 Public Libraries Consolidation (Scotland) Act which granted all local authorities the power to purchase, rent or construct libraries and to maintain and furnish them.

Training Library Staff

Carnegie’s philanthropy had indirect consequences too. With the establishment of so many new libraries, it became increasingly imperative to ensure that these were staffed adequately and professionally. In 1908, the Scottish Library Association was established bringing together all of those involved in the profession. This marked an important turning point for libraries and for those who worked in them. The SLA became the key professional forum for the sector, interested in the development and enhancement of libraries as well as the skills, knowledge and expertise of those who worked in them.

The library as a beacon of light

The First World War and its aftermath lead to many significant changes in society and libraries and librarians were not immune from this. In the difficult inter-War years, the public library network throughout Scotland had to adapt to tough fiscal times but also remain true to the ideals of education, entertainment and self-improvement. Carnegie had used the torch, a beacon of light, as a decorative device in many of his libraries. It is not an exaggeration to say that they were beacons of light during these dark inter-war years but they were also, for many, beacons of hope. Libraries were open to all, accessible to everyone, offered endless possibilities for socially-inclusive life-long learning (decades before those terms became fashionable).

Into the future

Scotland’s public libraries continue to play an important part in communities right across the country. They are accessible, neutral public spaces which enhance and enrich the lives of much of Scotland’s population. They have undergone enormous change with the advent of the internet and digital delivery, but consistent with previous times of challenge, they have admirably adapted and changed. Providing books, developing literacy, encouraging life-long learning, offering digital products and services – libraries will continue to be never failing springs and beacons of light for our communities.